I was recently asked to share some ideas for how to improve a skill I had written about previously in a leadership forum.

A person in leadership should be able to walk into just about any type of conversation with minimal knowledge of the topic and be able to contribute/participate (assuming the person facilitating the conversation knows how to lay out the challenge at the beginning of the conversation)

Kathy Keating, July 2018, Rands Leadership Slack, #leadofleads channel

Being effectively vocal in groups has been a skill that I’ve worked to improve my entire life. I test 100% introverted each time I take the Myer’s Briggs assessment, and I didn’t talk outside of my family unit until I was in the second grade. I am uncomfortable in large groups where I don’t know people, and I still avoid calling a business to get information. I almost never answer my phone unless I know the person who is calling. Yet…most people I interact with in a work setting are always very surprised to learn this about me since I’ve built the skills to offset this.

As a person moves up in their career, the competencies we must demonstrate around communicating effectively and cross-functionally increase. In senior individual contributor (IC) roles and in management roles we eventually get measured on these competencies, and our lack of proficiency can begin to adversely impact our pay and promotions.

Let’s take a look at how to increase these skills, and also look at why these skills are important to senior and management roles.

What are Effective Dialog Skills?

The Trainer’s Library suggests that there are seven skills that are critical to evolve if we want to be effective dialogue participants. This skills include:

- deep listening

- respecting others

- inquiry

- voicing openly

- balancing advocacy and inquiry

- suspending assumptions & judgements

- reflecting

During dialog we must both actively, and deeply listen. We must also examine what we are hearing to begin to form a perspective. Being able to balance our listening with our thinking is a skill that must be developed through practice and introspection. Especially if we want to do this quickly and in the moment.

One of the signs I often see from people who are just starting out on this journey is that their participation in a dialog is often one that is counter to the idea being presented. We begin to express to all the various reasons why the idea will not work. However at this point in a dialog we likely have very limited understanding of the big picture, nor all the different avenues the speaker has already examined. This approach often leads to less effective decision making overall and can actually erode trust across participants in the dialog.

Whether we are the initiator or the participant in the conversation, we must intentionally bring ourselves to the conversation with the mindset that we are, first and foremost, seeking to understand. We must also desire an outcome that focuses on finding most informed decision possible and not in being right.

Why are Effective Dialog skills important?

Collaborative communication leads to more effective decision making. When we make better decisions across our organization, friction decreases and productivity increases.

The progress we make in any area, work or personal, is a series of many decisions that add up to an outcome. If our initial decisions are faulty, then all the decisions that come after it are too. Sometimes we only get to positive outcomes after making 100s of decisions along the way.

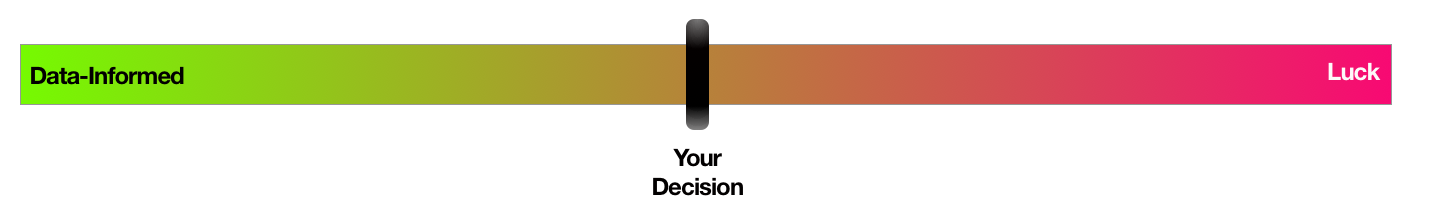

There are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about

Annie Duke, Thinking in Bets

At any given moment, for any given decision, we never have all the facts. There is always uncertainty, risk, uncontrollable factors, and sometimes even politics or deception. We must think of our decisions along a sliding scale ranging from fully-defined facts to luck. If we want to make sound decisions based on facts, then we have to bring data into our decision making process. We do this through effective cross-functional dialog.

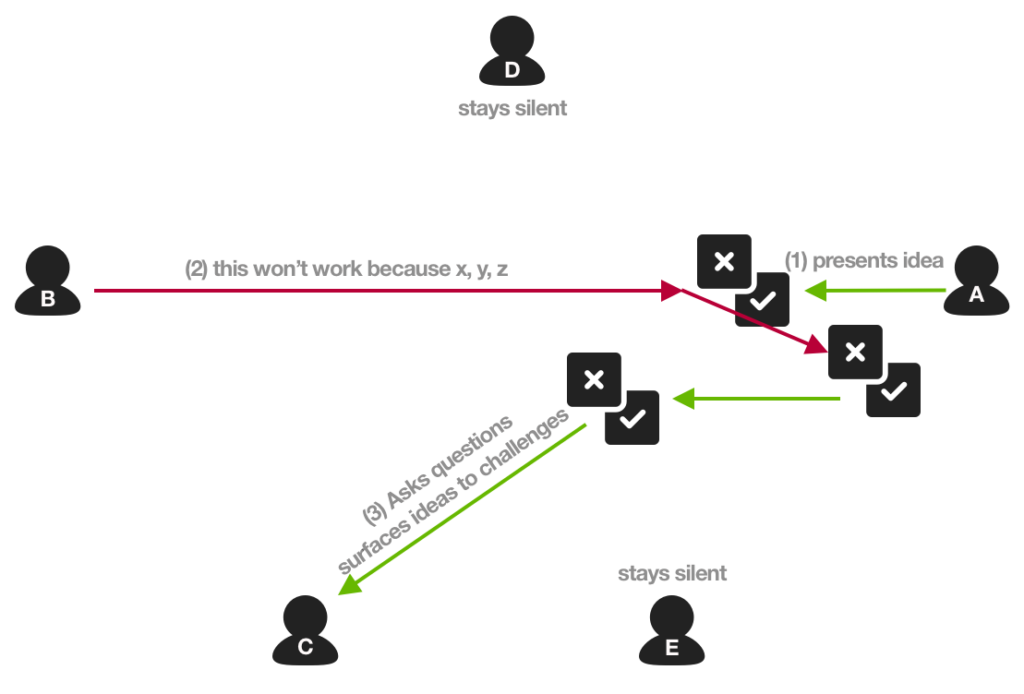

Lets examine what happens when an idea is put forth within a cross-functional dialog that is not effective.

- Person A surfaces an idea or challenge, and begins to start to present the data they have thus far.

- Person B has an immediate gut reaction to the idea, they stop listening, and begin to express all the reasons that the idea won’t work. Person A knows they haven’t shared all the data, but they feel confronted, and begin to back off.

- Person C recognizes that the conversation is not moving toward an informed decision, so they listen more deeply, formulate some options and begins to ask questions and advocate for solutions. This engages Person A to stay in the conversation and the idea moves a little further toward being data-informed.

- Persons D and E stay silent throughout the discussion. Their silence goes relatively unnoticed, and a decision is eventually made without taking into account the facts that Person’s D and E might have that would better inform a more sound decision. This is also the scenario that happens when key people are not consulting in a decision. The decision is less informed.

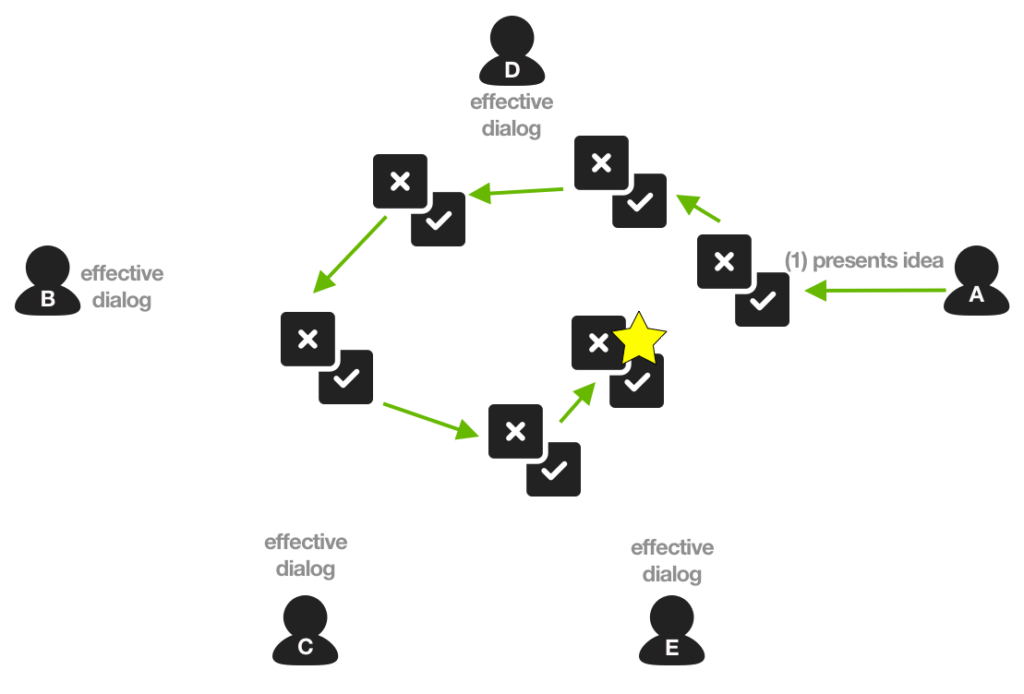

What would effective decision making look like? Effective decision making happens when all key parties that impact a decision are consulted. These parties remain open during the dialog, they actively and deeply listen to the challenge, they ask questions, and they form perspectives which they share. Because all parties are exchanging information effectively, the decision becomes more and more data-informed. And the team collectively is relying less and less on luck.

Eventually the decision is as informed as it’s going to get, luck is minimized and the decision can move forward effectively.

How do we build better Effective Dialog skills?

So how do we become more effective at cross-functional dialog? To become more effective at dialog, we want to focus on becoming better at making effective, data-informed decisions.

When presenting an idea, we have the choice to focus on (1) getting everyone to agree to our idea, or (2) gathering the data we need to make a sound, informed decision. Hopefully you want to focus on the latter perspective! Ways that we can build our data gathering skills are through the following practices:

- Intentionally decide who in our sphere could better inform our idea

- Seek these people out and ask for feedback on the idea

- Think cross-functionally. Don’t just talk to people in your role, or your group. Teams and companies are all affected by the decisions we make, so make sure all functions affected by the decision provide feedback

- Present the facts that you know thus far. Clearly share the open questions you know.

- Pause to provide others space and time to respond.

- Let ideas rise to their full potential. When we choose not to include others, whether intentional, or unintentional, we restrain our ideas from reaching their full potential.

- Converse with cross-functional groups. 1:1 conversations might feel safer, and they definitely inform initial thinking, but we eventually deprive the idea from reaching its full potential because ideas aren’t triggering new ideas, round-robin style, throughout the room. We want the thinking on our ideas to spread wide and deep so that we can capture all the data we need.

- Be efficient. Seek to get the most feedback from relevant areas. We will never be able to speak with everyone. Also, we must build the skill to assess when feedback is not relevant or helpful.

- Take notes while the idea is being presented. Have a Pros and Cons columns on the notes. We must remain open, require ourselves to listen deeply, and ensure our notes properly capture our thinking on both aspects of the idea – the pros and cons.

- Let the speaker present the idea. Don’t interrupt. The moment we judge an idea, we typically stop listening. In a productive conversation we’ll have ample time to respond.

- Most ideas are typically just a hypothesis the speaker has about how to tackle a narly challenge. We want to make sure we understand the underlying challenge. There are often 101 ways to address any problem.

- Once we collectively agree that the challenge is worth solving, we can collect all sorts of data to better inform a good decision.

If we initially confront ideas with judgement, we prevent ourselves from growing and learning. Our judgements are not data-informed decisions. They are merely potential risks to the viability of the idea coming to fruition. If we find yourself with a long list of “cons” about an idea, then we could begin to examine how each of these risks could be mitigated so the idea could move forward.

- Do other precursor projects exist that would have to be completed before the idea could be realized?

- Is there missing data that needs to be gathered?

- What adverse impacts are not yet being discussed? Bring this forward into the dialog.

When we stay silent we are choosing not to inform the idea. This also means that we’re responsible for the consequences that come from this decision. There are many reasons that people might stay silent – fear, indecision, politics, lack of trust, etc. Most often we stay silent because we don’t currently have a fully informed perspective.

The ability to transition quickly from hearing an idea to having a perspective is a learned skill. We build this skill through intentional practice. We have discussed previously how important active, deep listening and intentional note taking can be.

One way evolve our ability to ideate quickly and effectively is to challenge ourselves to express a perspective, under time pressure, on a random idea. Here are some ways to do this:

- Join Toastmasters and participate in Table Topics

- Get a peer group together. Each person writes a random topic on an index card. Each person draws a card one at a time. They have 1 minute to prep and 3 minutes to talk about the topic.

- Get a group of peers together. Everyone submits at least one slide for a slide deck. The moderator puts the slides into a random order and turns on a 1 minute rotation per slide. Participants draw randomly select an order to participate. The group collectively selects a discussion topic (e.g., engineers managers might select “project checkin”). Each speaker gets a slide, the slide comes up, the speaker speaks on the topic based on what they see, for the first time, on the slide. The speaker must speak for the full minute that the slide is up, then it moves onto the next speaker.

Yes, hilarity can ensue when a speaker gets a slide with an image of a dragon, or a topic that they know nothing about. These group settings are a safe place for us to learn, and get feedback from peers. The point is to help build the habit to be vocal, form ideas quickly, outline talking points, speak constructively, and productively seek resolution.

It is also a perfectly acceptable process to tell someone we need 24 hours to provide feedback.

Setting an Effective Dialog Goal

We all have different challenges when it comes to building more effective dialog. Let’s take a look at what a GEM might look like for someone who often is silent in meetings.

GOAL: I share my perspectives more often so that we can make more informed decisions as a team

EXPERIMENTS: In each cross-functional discussion where new ideas are presented I will:

- Take pro/con notes each time someone shares an idea.

- Ask at least two questions to ensure I fully understand the idea

- Reflect back to the team why the idea is important to make sure I understand what outcome we are solving for

- Express at least one perspective that furthers the idea forward to a more data-informed decision

MEASURES: I share my perspectives at least once in every meeting where a new idea is presented.

Writing our goals in this format creates an action plan that we practice every day to move ourselves further to building new habits in this area.

Making strong, data-informed decisions, and communicating effectively in the moment is definitely an art. All of us are somewhere on the continuum toward proficiency in this skill, and we are highly likely never to reach perfection. Language is an imperfect medium to communicate and everything can never fully be known.

For me, I’m a lifelong learner when it comes to this skill. Sometimes I come across as prescriptive which doesn’t great enough space for others perspectives to step in. Other times I take too long to form my perspective and I miss the decision. I can get a bit emotive when decisions are made without feedback that have adverse consequences.

The first step is recognizing when we falter, then stepping forward to do better the next day. I embrace that I’m gloriously imperfect at this. All I can do is be intentional – continue each day to learn, evolve and adapt while always staying focused on the mission before us.

Imagine what we could make happen if the world if we all embraced this perspective together? Whoa, what a world it would be.

Photo by Jens Lelie on Unsplash